Galileo's Revolutionary Cosmology

Written on

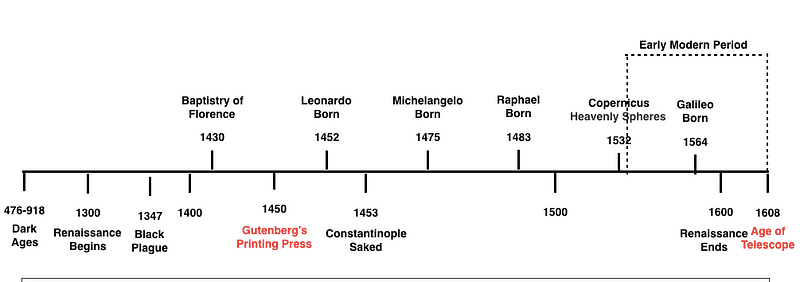

Chapter 1: The Context of Change

The Italian Renaissance marked a remarkable era of enlightenment that flourished for approximately three centuries, culminating in the birth of Galileo Galilei. By this period, Europe—and particularly the Catholic Church—had endured a tumultuous social upheaval, which culminated in a reactionary inquisition aimed at halting further transformations. However, change was not something that fit within Galileo’s perspective, even as "Church leaders" attempted to instill a fear of change within him.

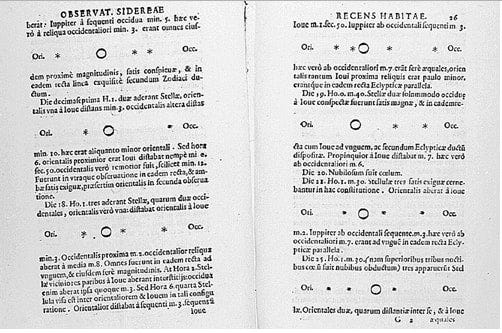

Sidereus Nuncius, commonly known as Starry Messenger, is a brief astronomical treatise published by Galileo on March 13, 1610. This work documented his early observations, revealing the Moon's rough and uneven surface, the countless stars invisible to the naked eye in the Milky Way and other constellations, and the Medicean Stars—later identified as Jupiter’s moons. In a letter dated January 7, 1610, Galileo described his telescopic findings:

“Many fixed stars become visible through the spyglass that are not perceived without it; just this evening, I observed Jupiter accompanied by three fixed stars, completely hidden due to their small size, arranged in this specific configuration.”

The illustration of Jupiter’s satellites from Sidereus Nuncius showcases Galileo Galilei’s sketches of the moons' shifting positions, observed through his telescope in 1610. This evidence clearly indicated that not all celestial bodies revolved around the Earth. It became apparent that Earth was not the sole planet to have moons, suggesting that regardless of one’s worldview, multiple centers of motion existed. In addition to detailing Jupiter's satellites, The Starry Messenger highlighted that the Milky Way was a vast assemblage of stars and that the Moon possessed a surface that was far from smooth, resembling Earth's terrain.

Responses to Sidereus Nuncius varied widely, ranging from praise to skepticism, quickly spreading across Italy and England. Several poems and texts celebrated this innovative approach to astronomy. Notably, three artworks were created in response to Galileo’s publication: Adam Elsheimer's The Flight into Egypt (1610), Lodovico Cigoli's Assumption of the Virgin (1612), and Andrea Sacchi's Divine Wisdom (1631).

Galileo's illustrations of a flawed Moon directly contradicted Ptolemy’s and Aristotle’s descriptions of flawless, immutable celestial bodies composed of quintessence (the fifth element in ancient and medieval thought).

“Prior to Sidereus Nuncius, the Catholic Church regarded the Copernican heliocentric model as purely mathematical and theoretical. However, as Galileo began to assert the Copernican perspective as a reality rather than a mere theory, it introduced a chaotic system that seemed less divine and orderly.” This Copernican view that Galileo advocated directly clashed with scripture, which spoke of the sun "rising" and the Earth as "unchanging."

Galileo was summoned to Rome on two occasions (1616 and 1632) to address the legitimacy of Copernicus’ theory. Following a review of Galileo's correspondence in February 1616, the Inquisition concluded that: the idea of a stationary Sun at the center of the universe was philosophically absurd and formally heretical, while the notion of a moving Earth was seen as philosophically absurd and at least theologically erroneous.

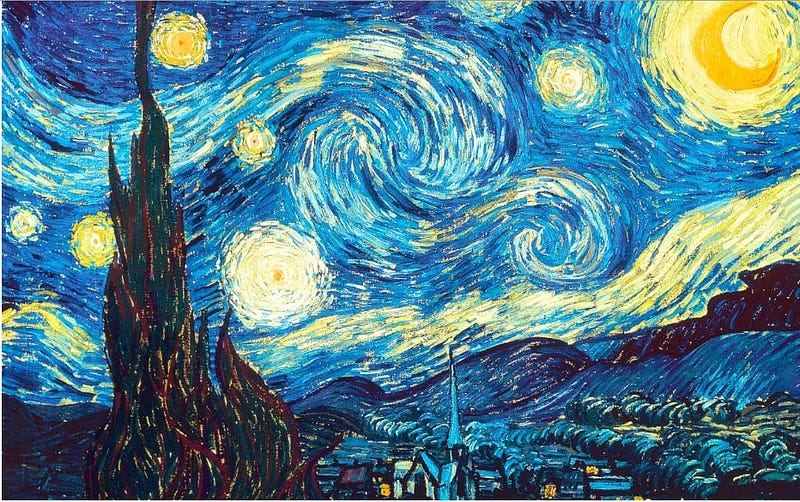

Two centuries after Galileo's passing, on May 8, 1889, Vincent van Gogh voluntarily admitted himself to the Saint-Paul de Mausole psychiatric institution in Saint-Rémy de Provence. Under the care of Dr. Théophile Peyron, he created numerous works inspired by the surroundings, both within the asylum and in the nearby landscapes, including olive groves and cypress trees.

Saint-Rémy served as the backdrop for many of van Gogh’s iconic pieces. After more than a year, he left for Auvers-sur-Oise on May 16, 1890, seeking to return north and feeling weary of the asylum. Dr. Peyron declared him cured.

It is believed that van Gogh’s Starry Night illustrates the view from his east-facing window in the asylum just before dawn. Although they never met, both Galileo and van Gogh seem to be connected through the lyrics of Don McLean’s “Vincent (Starry, Starry Night).”

“Starry, starry night

Portraits hung in empty halls

Frame-less heads on nameless walls

With eyes that watch the world and can’t forget

Like the strangers that you’ve met

The ragged men in ragged clothes

The silver thorn of bloody rose

Lie crushed and broken on the virgin snow

Now I think I know

What you tried to say to me

And how you suffered for your sanity

And how you tried to set them free

They would not liste